Date: 10. July 2025

Time to read: 3 min

Once, when the mountains still proudly wore their white caps, which are now disappearing at an accelerating pace, the Alps were covered by glaciers. These mighty and slow rivers of ice, like sculptors, smoothed valleys, cut walls and created the Alps as we know them today. They created the emerald green Lake Bohinj, the breathtaking valleys of Trenta, Vrata, Kot, Krma and the Logar valley. Without them, Slovenia would look very different today.

The last two pieces of the ice cap

Only two glaciers or glacial masses remain in Slovenia, the Triglav Glacier and the Skuta Glacier. Due to their small size, neither of them has the characteristics of glaciers anymore, i.e. they no longer move and have no glacial crevasses, so the two are now classified as ice patches or small glaciers. The two glaciers of today are a pale shadow of their former grandeur and living proof of the impact of climate change.

-

The Triglav glacier, or what remains of it, in the begining of September of 2024. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The Triglav glacier, or what remains of it, in the begining of September of 2024. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

The Skuta glacier in October of 2024. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The Skuta glacier in October of 2024. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

They have been carefully monitored and measured by experts of the Anton Melik Institute of Geography at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts since 1946. This is the oldest ongoing scientific research project in Slovenia.

The Triglav Glacier

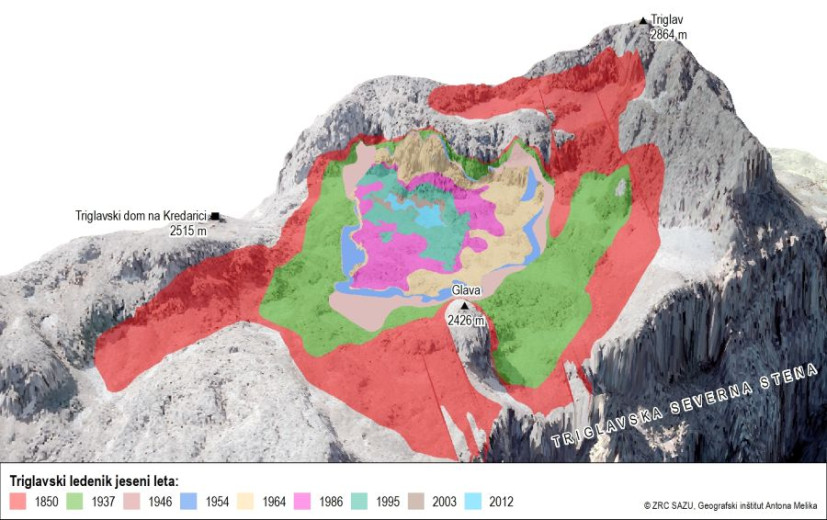

The Triglav Glacier lies below Mount Triglav, Slovenia's highest peak. It is the remnant of what was once a much larger glacier. In the middle of the 19th century, it covered more than 40 hectares; at the beginning of the regular measurements, it was just 14 hectares, but by now it has shrunk to less than 0.2 hectare. Today, many visitors to Mount Triglav do not even notice the ice patches.

-

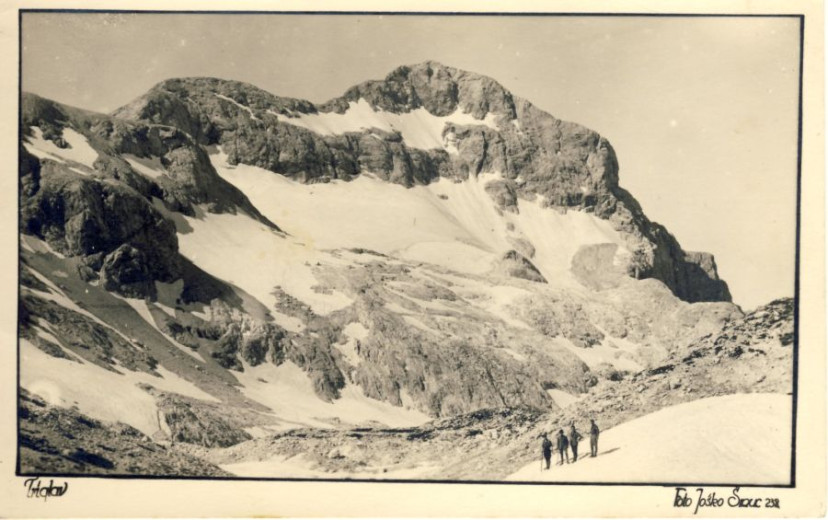

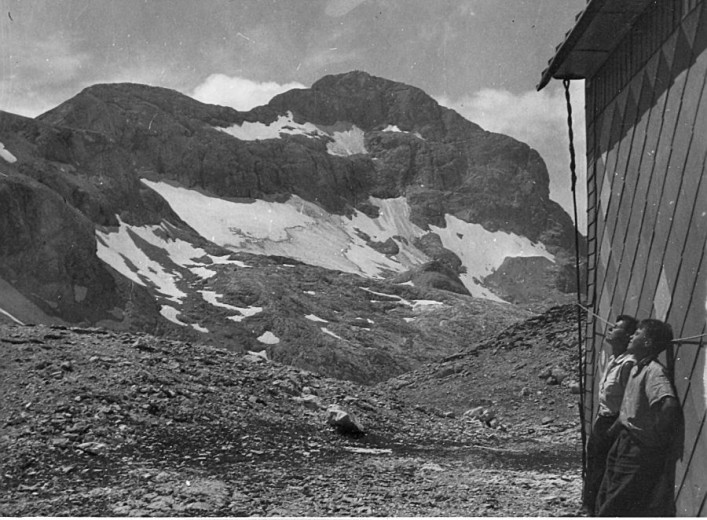

The photograph shows the Triglav Glacier in 1940, when the glacier covered a large portion of the slope beneath Mount Triglav. Photo: Joško Šmuc, Krištof Kranjc collection, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The photograph shows the Triglav Glacier in 1940, when the glacier covered a large portion of the slope beneath Mount Triglav. Photo: Joško Šmuc, Krištof Kranjc collection, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

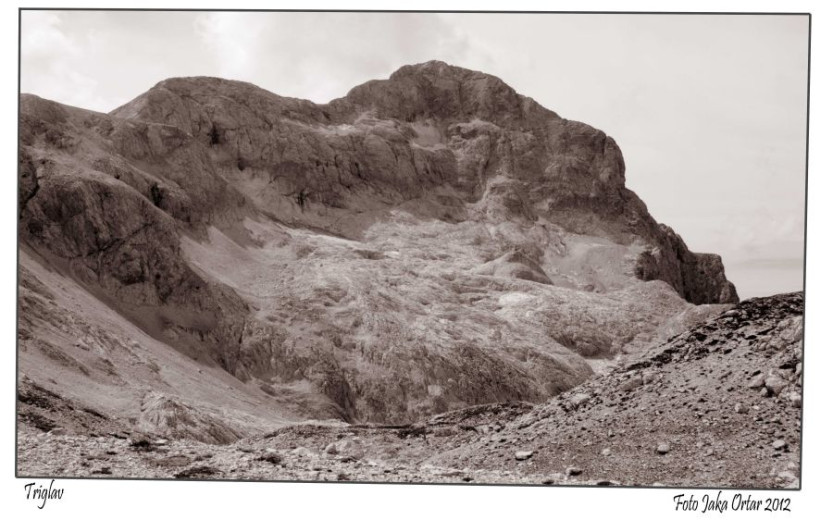

Photo made in retro style shows the size of Triglav Glacier in 2012. Photo: Jaka Ortar, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

Photo made in retro style shows the size of Triglav Glacier in 2012. Photo: Jaka Ortar, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The Triglav Glacier was originally known as the Green Avalanche or the Green Snow. It is so named because of its green colour of firn ice, a transitional form between snow and glacier ice. Firn turns into glacier ice over the years or, on the south-eastern margin of the Alps, even decades.

-

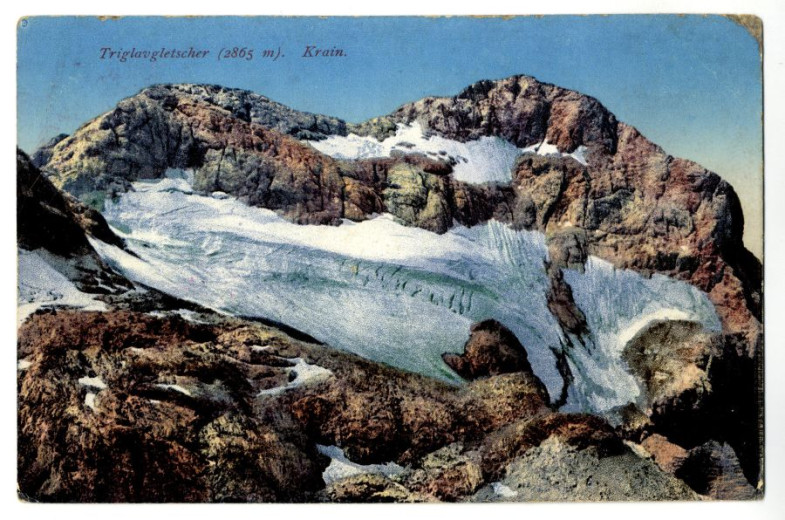

A postcard from 1897 clearly showing the former extent of the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Alois Beer, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

A postcard from 1897 clearly showing the former extent of the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Alois Beer, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

-

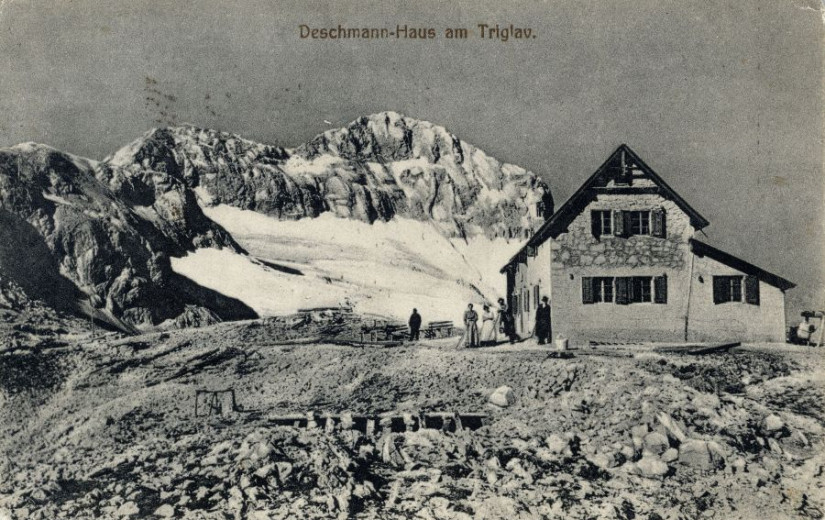

A postcard sent in 1910 depicting the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Fran Pavlin, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library, (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

A postcard sent in 1910 depicting the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Fran Pavlin, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library, (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

-

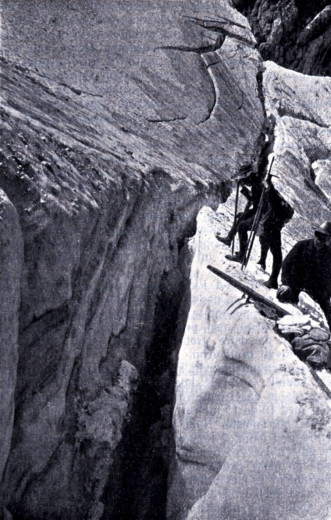

A 1923 photo of the Triglav Glacier reveals its once-mighty expanse, marked by deep crevasses that capture the glacier’s former grandeur. Photo: Josip Kunaver, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

A 1923 photo of the Triglav Glacier reveals its once-mighty expanse, marked by deep crevasses that capture the glacier’s former grandeur. Photo: Josip Kunaver, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

-

An image of the Triglav Glacier from the mid-1920s, offering a glimpse into its once-magnificent past. Photo: Unknown author, Archive of Slovenian Alpine Museum (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

An image of the Triglav Glacier from the mid-1920s, offering a glimpse into its once-magnificent past. Photo: Unknown author, Archive of Slovenian Alpine Museum (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

-

View of the Triglav Glacier from the Stanič Hut, August 1957. Photo: Vlado Pavšek, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

View of the Triglav Glacier from the Stanič Hut, August 1957. Photo: Vlado Pavšek, Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The shrinkage of the Triglav Glacier started to intensify in the 1990s. The increasingly rapid thinning of the ice caused the appearance of outcropping rocks in the centre and the glacier split into two parts in 1992. Between 1952 and 2003, the volume of the glacier decreased by about 100 times. Its small size makes it extremely vulnerable to climate change. Researchers reckon that we are probably one of the last generations with the chance to see its remnants in person. If global warming is as intense as it has been so far, the glacier will eventually disappear.

-

A photo of the Triglav Glacier from 1954. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A photo of the Triglav Glacier from 1954. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

A photo of the Triglav Glacier taken in September 1975, clearly showing its reduced size compared to the previous image. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A photo of the Triglav Glacier taken in September 1975, clearly showing its reduced size compared to the previous image. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

A photo of the Triglav Glacier from September 2016, highlighting its diminished size. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A photo of the Triglav Glacier from September 2016, highlighting its diminished size. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

The photo from 2022 captures the final remnants of the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The photo from 2022 captures the final remnants of the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

A 2023 photo reveals the inevitable fate of the Triglav Glacier, showing by a scree covered remaining patches of ice on the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A 2023 photo reveals the inevitable fate of the Triglav Glacier, showing by a scree covered remaining patches of ice on the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Camera Triglav Glacier (http://ktl.zrc-sazu.si/), archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The Skuta Glacier

The Skuta Glacier in the Kamnik-Savinja Alps is the most easterly glacier in the Alps. Although it was once smaller than the Triglav Glacier, it is now the largest glacier in Slovenia. At an altitude of 2100 metres, it is 400 metres lower than the Triglav Glacier, but it has an important advantage - a more favourable, shady position that slows down the glacier's melting.

Its relatively low altitude makes it particularly vulnerable to climate change. In 1950 it covered an area of 2.8 hectares, today it covers 1.3 hectares.

Even more than the surface, the thickness of the glacier is changing. Experts of the Anton Melik Institute of Geography at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts estimate that it is decreasing at an average rate of 1-1.5 metres per year in different parts of the glacier.

-

A 1913 photo of the Skuta Glacier shows mountaineers walking along the edge of a deep crevasse, searching for a missing person. Photo: Josip Kunaver, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

A 1913 photo of the Skuta Glacier shows mountaineers walking along the edge of a deep crevasse, searching for a missing person. Photo: Josip Kunaver, Cartographic and Image Collection of the National and University Library (Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography)

-

A 1982 photo of the Skuta Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A 1982 photo of the Skuta Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

This 2023 photograph reveals how much the Skuta Glacier has diminished. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

This 2023 photograph reveals how much the Skuta Glacier has diminished. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

2025 International Year of Glacier Conservation

Glaciers are natural reservoirs of fresh water, containing almost three-quarters of the Earth's fresh water. They regulate the climate by reflecting sunlight to cool the planet. They are an indicator of climate change. But in recent decades, they have been disappearing before our eyes at an accelerating rate. According to the World Meteorological Organisation, last year, the ice mass declined for the third year in a row in all glacier areas around the world.

Miha Pavšek from the Anton Melik Institute of Geography at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts estimates that in case, the rest of the summer continues to be excessively hot, the last patches of ice beneath Triglav could disappear already by the end of this summer, and those beneath Skuta in the next few years.

-

The retreat of the Triglav glacier between 1850 and 2012. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

The retreat of the Triglav glacier between 1850 and 2012. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

-

A photo taken in September 2023 showing the remaining patches of ice on the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

A photo taken in September 2023 showing the remaining patches of ice on the Triglav Glacier. Photo: Archive of Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, Anton Melik Institute of Geography

Since the mid-19th century, glaciers around the world have declined significantly. Satellite imagery shows that glaciers have decreased in thickness by an average of about 14 metres since 1976.

This has enormous consequences for people and ecosystems. Some projections suggest that by 2050, areas where 300 million people live today will be, due to the sea level rise - as a consequence of the water, coming from the thawing glaciers, below the average annual coastal flood level. The melting of permafrost and glaciers in mountains is creating more and more glacial lakes, which pose a greater risk of flooding in the event of a sudden spill.

A piece of the Triglav Glacier in Beijing

As glaciers are one of the best indicators of climate change, the Slovenian Olympic Committee has launched a special campaign ahead of the 2022 Winter Olympics in Beijing. At that time, a piece of ice from the Triglav Glacier was sent on a 36-day journey through nine countries to Beijing. This was to highlight that environmental change is not only a huge challenge for the organisation and delivery of such events, but also for the existence of certain disciplines.

Besides that, many ice samples of the Triglav Glacier were taken by the team from Anton Melik Institute of Geography at the Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts as part of an independent survey of Slovenian glaciers. The ice was exhibited in Beijing, melted slowly during the Games, symbolically pointing out the consequences of the changing atmosphere, and after the Games it returned to Slovenia and is exhibited as glacial water in the Slovenian Alpine Museum in Mojstrana.