Date: 1. November 2019

Time to read: 5 min

Painted beehive panels are an essential element in the history of Slovenian beekeeping and even in the history of Slovenian folk spiritual culture. These panels are the same to the fine arts as songs and tales are in literary folk art. But the images from beehive panels tell a special story of Slovenian history, ideas, beliefs and customs. They are unique historical records.

The art of painting beehives most likely began towards the end of the 18th century, in the golden age of baroque culture. The oldest beehive known today originates from 1758 and depicts an image of the Virgin Mary with a child. The classical period of painted beehive panels were the first three quarters of 19th century, especially the years between 1820 and 1880. Given that Anton Janša was from the Gorenjska region, this art probably also started in the Slovenian Alps, particularly in the hills behind Radovljica and Kranj and right up to the border with the Pannonian plain. Decorating the panels soon spread over the Karawanks into Koroška. However, none can be found in the flatlands of Slovenia, in Pannonia, the eastern Dolenjska region, or Bela krajina.

Marking of beehives

Beehives were supposedly painted primarily for bees to recognise their own beehive and for beekeepers to easily distinguish between individual beehives, but also to protect them against curses and accidents.

The first images on the panels were mainly religious with simple stories, but they were well-thought-out in a decorative sense. An image of Madonna or one of the Saints is usually in the middle and on both sides there are bouquets or vases with flowers or part of a curtain.

Also typical are pastoral images from the life of the rural population, particularly images of significant life events. Landscape and nature are rare, usually only as the background for the story. There are no portraits. Also vanity and embellishment can seldom be found, as this was not a part of rural life (the only exception is the story about the mill and desire for youthfulness and beauty). The most frequent motif is punishment. Since the beekeepers were men, the images are mostly about their view of life situations and attitude towards the opposite gender. However, there are not erotic motifs. Also motifs depicting beekeeping itself are infrequent.

For beehive panels making usually the wood of spruce was used and in rare cases also wood of linden, pine or larch. Experienced painters prepared their own quality paints. They finely ground the base paints and mixed them with linseed oil. This durable technique made it possible for images to defy sun and rain. Panels that were later painted with industrial paints are significantly less persistent.

The composition, layout of the figures, decoration and colour of beehive panels are all based on the baroque tradition. The significant fact here is that the painters, either professional or casual, didn’t want to create "works of art".

For them, the most important was the content. Nevertheless, all panels are beauteous and reflect almost intimate character. The paintings on beehive panels are not just folk art but also fine art.

Together with countless village churches and hay racks, the bee houses are typical element of Slovenian rural architecture and a recognisable symbol of Slovenia. Almost every farm used to have a bee house in times past.

Religious stories from beehives

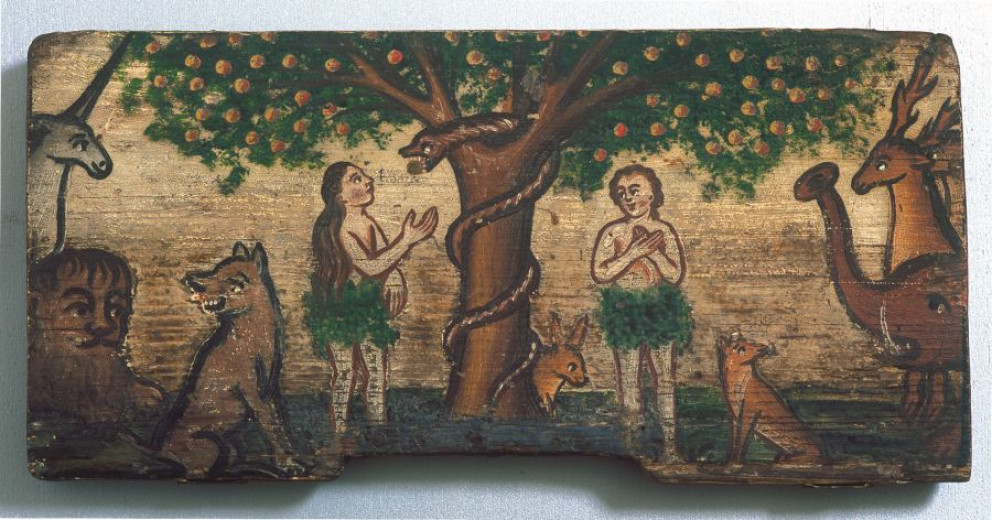

The Old Testament and the New Testament served as an inexhaustible source for beehive panel painters. Very popular was the story of original sin, in which Adam and Eve, encouraged by the snake, consumed the forbidden fruit and thus enraged God, who banished them from the Garden of Eden. Also frequent was the story about the Great Flood and Noah's Ark, as well as about Moses, who led the Exodus of the Israelites out of Egypt. One of the most frequent depicted patrons was Job. This is a story about old Job, who sits on a pile of manure and pays off for his wife with a fistful of worms. In Slovenia Job was considered the protector of the beekeepers until around the 19th century. Also John the Baptist, a forerunner of Jesus Chris, appears quite frequently. He became the protector of tailors, tanners, furriers, innkeepers, and capital convicts, as well as the protector of sources of water.

Among the most popular motifs are the images of patron saints.

One of the most depicted is St Florian, who protects mankind against earthly and eternal flames. Florian’s Sunday was also a holiday of shepherds. Also cellarers, soldiers and brewers considered him their protector. He is depicted as a warrior with a bucket, who extinguishes a house that is on fire. Saint Anthony of Padua is one of the emergency interveners. In Slovenian folk tradition he appears in "The Legend of Smlednik". The Baron from Smlednik demands a tax from the farmer, who already paid it to the baron’s deceased father. The farmer seeks protection from the saint, who orders the devils to bring the old baron from hell to confirm the farmer’s statements. Also popular is St George, the patron against contagious diseases, death at sea and in war, those in mortal danger, the protector of soldiers and crusaders, and, in Slovenian folk tradition, the protector of fields and cattle.

Among the female saints the most frequently appearing are St Catherine and St Barbara. According to legend, Catherine of Alexandria was so learned that merely through discussion she converted to Christianity 50 philosophers who tried to convince her of the superstition of Christianity. The Roman emperor Maxentius thus ordered her torture on a spiked breaking wheel, but as the lightning of heaven shattered the device, he ordered her to be beheaded. Her attributes are therefore a torturing wheel and a sword. St Barbara is a patroness of the miners, towers, farmers, architects, construction workers, girls, prisoners, artillery, fortresses, firefighters and the dying. Her attributes are a three-windowed tower, chalice and host, sword and torch, gun barrel or peacock's feathers, long coat and a head-covering. Also quite common are depictions of St Lucia and St Agnes. As the legend goes, Lucia gouged out her own eyes, as they had charmed one of her suitors, and she sent them to him. The young man converted to Christianity. She is thus frequently shown holding her eyes on a plate. Folk tradition describes her as the protector of sight.

Another rather frequent image is the end of the world. Christ as a judge will divide the entire human race, risen from the dead, based on the goodness or wickedness of their deeds, and condemn them to eternal glory or punishment.

Profane motifs

Those motifs derive from folk storytelling and everyday life or imitate important events. One of the oldest profane motifs is Pegam and Lambergar. Folk song describes their combat. In all probability it is about the historical battles between the Habsburgs and the Counts of Celje, who in 1418 as the heirs of the Ortenburgs enlarged their properties, particularly in Carniola. Another historical scene is that of the execution of the Austrian archduke Maximilian in Mexico. A reflection of the Counter-Reformation is also the depiction of Martin Luther and his spouse Katharina von Bora taken to hell by the devils. This motif is of a humiliating nature.

Profane motifs often include humorous stories, scenes of soldiers and scenes from everyday or festive village life (work of farmers, marriage, scenes from inns).

The motif of two soldiers leading prisoner reflects the violent recruitments into foreign armies after the introduction of general military duty in the last quarter of 18th century.

A special category is made up of images that scoff at human weaknesses or faults. Interesting is the story of Old Woman's Mill. Rural citizens probably understood the motif as punishment for female nagging. The mill as a rejuvenating instrument is derived from original forges, where old people were reforged into young ones with the help of fire.

Litigious passion is shown by the motif of two farmers quarrelling over a cow being milked by a lawyer. This motif also depicts the Slovenian saying that when two people are fighting over something, the third party wins all.

At the end of winter and the beginning of spring most customs are connected to Shrovetide period and its patron "Pust". He is depicted wearing a fool's cap with bells. His holiday is Shrove Tuesday, distinguished by parades of carnival costumes, and it ends on Ash Wednesday with the burning of a straw effigy representing the "Pust". Wearing masks has its roots in the beliefs that the spirits of ancestors and fertility spirits could only be approached by a man wearing a mask.

Also interesting is the image of "sawing the witch". On Ash Wednesday a log or a wooden board with a painted witch or straw effigy is cut in half and thrown into water, which symbolizes that one half of the unpopular fasting has already passed. This custom should be understood as driving out the winter.

Quite an old motif is a battle over a pair of trousers. The Slovenian folk version includes two women. The motif of derision shows the desire for marriage, but also has deeper background in conditions where unmarried women weren’t provided with social security. Also the motif of boiling a soup of trousers and the motif of a boy who is catching girls with trousers on a hook have similar meaning. However, marriage is considered to be one of the most important and happiest moments of life.

Beehive panels are actively painted in Slovenia even today, although with different stories and more pastoral images. Modern Slovenian apiculture indicates the value of this profession as well as the awareness that bees are an important part of nature.